By Brother David L. Carl

1-93-G

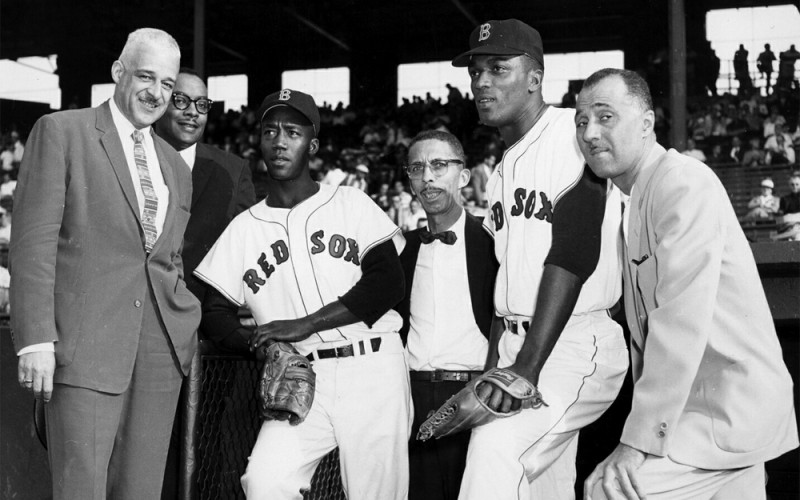

Members of the Boston branch of the NAACP greet Pumpsie Green and Earl Wilson of the Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park, 1959. From left: Herb Tucker, Harold Vaughn, Pumpsie Green, Ed Cooper, Earl Wilson, and Otto Snowden. Freedom House Collection, Northeastern University

Herbert E. Tucker, Jr., born in the era of a sharply segregated Boston, ascended from the position of a redcap toting bags in South Station, to a civil rights attorney and judge. Throughout his life, he worked tirelessly with his childhood friend and fraternity brother, Otto Snowden, to bring equity to the children of Boston, and place his community of Roxbury in the political forefront. In 1959, they took on the Boston Red Sox, and began to dismantle the 50 year legacy of racial segregation and intolerance.

After Jackie Robinson broke the color line, and the rest of the league integrated, Boston remained an all-white club for over a decade. Despite having the opportunity to sign Black players including Jackie Robinson and Willie Mays, who’s undeniable talent had potential to improve Boston’s failing teams, the franchise’s decision makers refused to hire Black players. This legacy of discrimination continued until 1959, making Boston the last team to integrate.

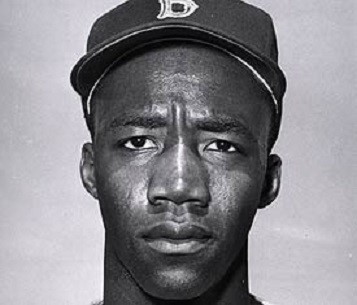

When the Red Sox invited Elijah “Pumpsie” Green to Spring training camp, the issue of race took center stage. Green, forced to stay and eat alone in rooming accommodations miles from the team’s hotel, endured social isolation and open hostility. Despite playing well and receiving much media attention, on April 7, the Red Sox optioned him to their Triple-A farm club, explaining they felt “the first Negro to wear a Red Sox uniform needed more seasoning”.

Immediately upon Green’s demotion, Herbert Tucker, then president of the Boston branch of the NAACP, took swift action. He waged opposition to the Red Sox’s use of a newly proposed parking lot based on the treatment of Green. Tucker told the Globe, “We feel very strongly that any business that would sacrifice the principles of fair play and the American way of life—as was evidenced in the treatment accorded Pumpsie Green during the Spring training season and the subsequent results thereof—should not be allowed to benefit financially by utilizing public lands for their private use.”

Elijah “Pumpsie” Green

Tucker demanded an investigation of the Red Sox for alleged discrimination. He cited a 12-year history of continue discrimination even after Major League had integrated. The Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination (MCAD) commenced a public hearing into the Red Sox’s hiring practices of both the players and Fenway Park staff. Tucker argued the Red Sox had an anti-Negro policy and chastened that it remained the only team without a Negro player. Tucker said the Red Sox rejected Jackie Robinson, Sam Jethroe, and Willie Mays, all of whom became stars. This could only be explained by a pattern of explicit racism or complete managerial incompetence.

As the Red Sox opened the season with poor play, a reporter asked manager Pinky Higgins if he had considered recalling Green. He responded by openly calling the reporter a “nigger lover.” However, amidst continued pressure from Tucker and his coalition of civic groups and political organizations, when the team continued to struggle, management finally conceded. It replaced the manager, and three weeks later, on July 21, 1959, Pumpsie Green entered the game making Boston the last team in the major leagues to end the color barrier. One week after Green’s promotion, the Red Sox brought in their second Black player in pitcher Earl Wilson.